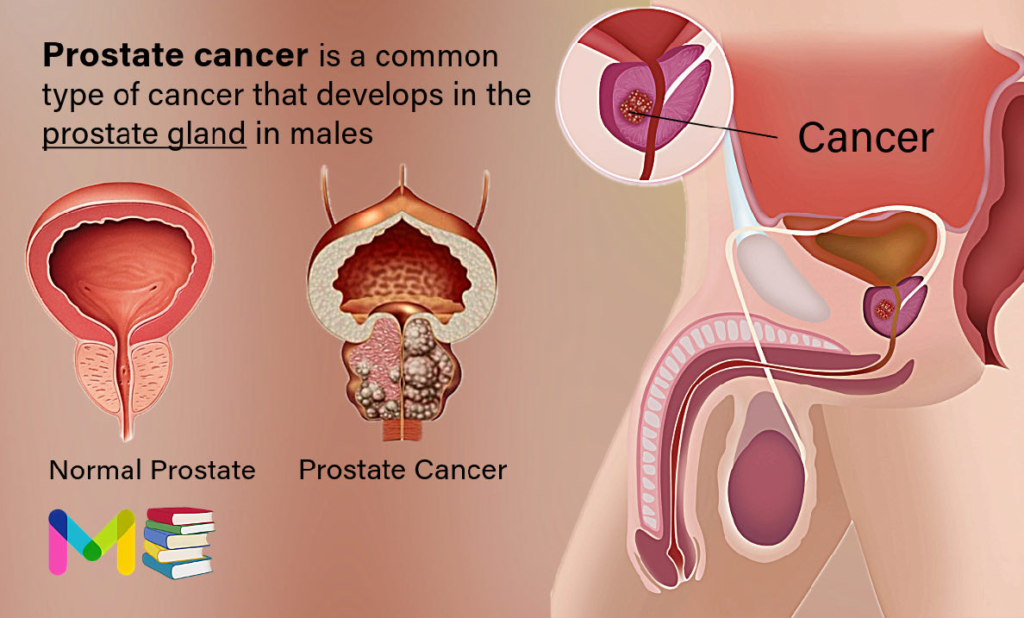

Prostate cancer is a common type of cancer that develops in the prostate gland in males. The prostate is a small walnut-shaped gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum in males. This tiny gland secretes fluid that mixes with semen, keeping sperm healthy for conception and pregnancy.

Prostate cancer usually doesn’t cause symptoms until it’s grown large enough to press against your urethra. When this happens, you may have symptoms such as trouble urinating or not feeling like you’ve completely emptied your bladder.

Prostate cancer is common, second only to skin cancer as the most common cancer affecting males. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for every 100 males, 13 will develop prostate cancer at some point in their lives. Most will live normal lives and eventually die from causes unrelated to prostate cancer. Some won’t need treatment.

About 80 percent of prostate cancers are diagnosed at a localized stage, which means that the cancer hasn’t spread outside of the prostate. The average age at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis is about 66.

According to The National Institute on Aging, prostate problems are common after age 50. However, learning more about prostate cancer and prostate-related health issues can help optimize health.

Table of Contents

Key points about Prostate Cancer

- Prostate cancer is a common type of cancer that develops in the prostate gland in males.

- The risk of prostate cancer increases with age, particularly after age 50.

- Experts aren’t sure what causes cells in your prostate to become cancer cells. As with cancer in general, prostate cancer forms when cells divide faster than usual. While normal cells eventually die, cancer cells don’t. Instead, they multiply and grow into a lump called a tumor. As the cells continue to multiply, parts of the tumor can break off and spread to other parts of your body (metastasize).

- The different types of prostate cancer are categorized depending on the type of cell in which they originate. The main type is called adenocarcinoma.

- In the early stages, prostate cancer often doesn’t cause any noticeable symptoms. As the cancer grows, it can lead to problems with urination, pain, and other issues.

- Common ways to diagnose prostate cancer include a digital rectal exam (DRE), a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test, and a biopsy.

- Treatment options for prostate cancer depend on several factors, including the stage and grade of the cancer, the patient’s age and overall health, and their preferences.

Key points about Urinary Incontinence

Types of Prostate Cancer

The different types of prostate cancer are categorized depending on the type of cell in which they originate. The main type is called adenocarcinoma, making up about 95% of all diagnosed prostate cancers.

Less common types include:

- transitional cell carcinoma

- squamous cell carcinoma

- neuroendocrine prostate cancer

- sarcoma

- lymphoma

Some types can grow and spread quickly, but most are slow growing.

Adenocarcinoma of the prostate

Adenocarcinomas are by far the most common type of prostate cancer. They develop within the gland cells in the prostate that make the prostate fluid that’s added to semen. Adenocarcinoma is typically slow growing and less aggressive than other types of cancer, with a high survival rate.

There are two subtypes of prostate adenocarcinoma, which include:

- Acinar adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma (PAC) develops from the acinar epithelium, a layer of outer cells that line the prostate gland. People with this subtype tend to live longer and avoid the spread of cancer to other organs more often than the other subtype.

- Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Ductal adenocarcinoma (DAC) is considered to be rare and more aggressive. It develops in the ducts, or tubes, of the prostate gland and is characterized by tall, stacked columns of atypical epithelial cells. It’s known to occur alongside PAC. It’s more difficult to detect in earlier stages. DAC is more likely to reoccur and spread to distant tissues than PAC. This makes it more dangerous and leads to lower survival rates. Additionally, DAC doesn’t respond as well as PAC to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), a type of hormone therapy used in treatment. Despite this type of cancer being rare, it’s still the second most common type of prostate cancer.

Neuroendocrine prostate cancer

Neuroendocrine prostate cancer originates in the prostate’s neuroendocrine cells. These cells receive signals from the nervous system to release hormones.

These cancers are more difficult to detect with a blood test because neuroendocrine cells don’t involve elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels like other prostate cancers. Neuroendocrine cells don’t make PSA like other cell types.

Neuroendocrine prostate cancer is highly aggressive and quickly spreads to other organs. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified four subtypes:

- Small cell carcinoma: The most aggressive type, small cell carcinoma often spreads to other parts of your body, like your bones, and doesn’t respond well to treatment with ADT. The average age at diagnosis is 70 years, according to a 2019 study.

- Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: This subtype type most commonly occurs as a result of ADT for other prostate cancers.

- Adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: This subtype contains both adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor components.

- Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors: These comprise cells that appear like normal cells but can act aggressively.

Transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate

Transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate, also called urothelial carcinoma, originates in the cells that line the urethra, the tube that carries urine outside your body.

This type of cancer usually starts in the bladder and spreads into the prostate. This means that if a doctor discovers it in the prostate, it’s usually already spread from somewhere.

Rarely, it can start in the prostate and spread into the bladder and nearby tissues.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate

Squamous cells are thin, flat cells that make up the outermost layer of various organs. This type of cancer is most common in the skin, but it can also affect your prostate, lungs, mucous membranes, digestive tract, and more.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate begins in cells that cover the prostate. This type of cancer typically spreads faster, particularly to your bones, and is more aggressive than adenocarcinoma.

Sarcoma of the prostate

Also called soft tissue sarcoma, sarcomas are cancers that originate from soft tissues, such as the:

- muscles

- nerves

- blood vessels

- fibrous tissue

- fat

- joint lining

- lower levels of the skin

They can develop anywhere on your body, including the prostate. There are several types, including:

- Leiomyosarcoma. Which is aggressive and can spread elsewhere on the body

- Rhabdomyosarcoma. Which is also aggressive and most common in children

Lymphoma of the prostate

Lymphoma is cancer of the lymph nodes. According to a 2022 study, it only affects the prostate in around 0.1% of newly diagnosed lymphomas. Due to its rarity, it’s difficult to differentiate between this type and other types. More research into this condition is needed.

Precancerous prostate conditions

Some prostate cancers might begin as a precancerous condition, which a doctor might discover with a prostate biopsy. There are two known types:

- Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN): When seen under a microscope, prostate cells don’t look normal or healthy, but they also don’t appear to be attacking other parts of the prostate like cancerous cells do. There are two types of PIN:

- low grade PIN. if the patterns of cells appear close to normal

- high grade PIN. if the patterns of cells look more atypical (this type may increase the risk of developing prostate cancer)

- Proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA): Under a microscope, prostate cells appear smaller than normal, and there are signs of inflammation. Medical researchers are still trying to determine if PIA can lead to PIN or prostate cancer.

Symptoms of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer may not cause symptoms at first. Most prostate cancers are found at an early stage. This means that the cancer is only in the prostate. An early-stage prostate cancer often doesn’t cause symptoms.

When they happen, early-stage prostate cancer signs and symptoms can include:

- Blood in the urine, which might make the urine look pink, red or cola-colored.

- Blood in the semen.

- Needing to urinate more often.

- Trouble getting started when trying to urinate.

- Waking up to urinate more often at night.

If the prostate cancer spreads, other symptoms can happen. Prostate cancer that spreads to other parts of the body is called metastatic prostate cancer. It also might be called stage 4 prostate cancer or advanced prostate cancer.

Signs and symptoms of advanced prostate cancer can include:

- Accidental leaking of urine.

- Back pain.

- Bone pain.

- Difficulty getting an erection, called erectile dysfunction.

- Feeling very tired.

- Losing weight without trying.

- Weakness in the arms or legs.

Make an appointment with a doctor or other healthcare professional if you have any symptoms that worry you.

Not all growths in your prostate are cancer. Other conditions that cause symptoms similar to prostate cancer include:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): At some point, almost everyone with a prostate will develop benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). This condition enlarges your prostate gland but doesn’t increase your cancer risk.

- Prostatitis: If you’re younger than 50, an enlarged prostate gland is most likely prostatitis. Prostatitis is a benign condition that causes inflammation and swelling in your prostate gland. Bacterial infections are often the cause.

Read article on: Types and Causes of Kidney Stones

Stages of Prostate Cancer

Your healthcare team uses the results of your tests and procedures to give your cancer a stage. The cancer’s stage tells your healthcare team about the size of the cancer and how quickly it’s growing.

To decide your prostate cancer stage, your healthcare team uses these factors:

- How much of the prostate contains cancer.

- Whether the cancer has grown beyond the prostate, such as into the rectum, bladder or other nearby areas.

- Whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

- Whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones.

- The level of PSA in the blood.

- The grade group.

Prostate cancer stages range from 1 to 4. A lower number means the cancer is small and only in the prostate. A lower number stage typically means the cancer is very likely to be cured. If the cancer grows larger or spreads, the stage goes up. A higher number stage may mean a cure is less likely. Your prognosis depends on many factors, so talk about this with your healthcare team.

The stages of prostate cancer are:

- Stage 1 prostate cancer. A stage 1 prostate cancer means the cancer is small and only in the prostate. The cancer only affects one side of the prostate gland. The PSA level is low and the grade group is 1.

- Stage 2A prostate cancer. A stage 2A prostate cancer may be a small cancer that only affects one side of the prostate, but the PSA level is intermediate. This stage also can mean that the cancer affects both sides of the prostate, but the PSA level is low. At this stage, the grade group is 1.

- Stage 2B prostate cancer. A stage 2B prostate cancer is only in the prostate. The cancer may have grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland. At this stage, the PSA level is intermediate. The grade group is 2.

- Stage 2C prostate cancer. A stage 2C prostate cancer is only in the prostate. The cancer may have grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland. The PSA level is intermediate. The grade group is 3 or 4.

- Stage 3A prostate cancer. A stage 3A prostate cancer is only in the prostate. The cancer may have grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland. The PSA level is high. This stage includes grade groups 1 to 4.

- Stage 3B prostate cancer. A stage 3B prostate cancer has grown beyond the prostate. The cancer might extend to the seminal vesicles, bladder, rectum or other nearby organs. The PSA level may be low, intermediate or high. This stage includes grade groups 1 to 4.

- Stage 3C prostate cancer. A stage 3C prostate cancer has a grade group of 5. It includes any size prostate cancer. The cancer may have grown beyond the prostate, but it hasn’t spread yet.

- Stage 4A prostate cancer. A stage 4A prostate cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

- Stage 4B prostate cancer. A stage 4B prostate cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones.

Read article on: Stages of Tuberculosis

Causes of Prostate Cancer

Experts aren’t sure what causes cells in your prostate to become cancer cells. As with cancer in general, prostate cancer forms when cells divide faster than usual. While normal cells eventually die, cancer cells don’t. Instead, they multiply and grow into a lump called a tumor. As the cells continue to multiply, parts of the tumor can break off and spread to other parts of your body (metastasize).

Luckily, prostate cancer usually grows slowly. Most tumors are diagnosed before the cancer has spread beyond your prostate. Prostate cancer is highly treatable at this stage.

Risk factors of Prostate Cancer

Some risk factors may affect your chances of developing prostate cancer, including your:

- family history

- age

- race

- geographical location

- diet

Family history

In some cases, the mutations that lead to prostate cancer are inherited. If you have a family history of prostate cancer, you’re at increased risk of developing the disease yourself, because you may have inherited damaged DNA.

According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 5-10 percent of prostate cancer cases are caused by inherited mutations. It’s been linked to inherited mutations in several different genes, including:

- RNASEL, formerly known as HPCI

- BRCA1 and BRCA2, which have also been linked to breast and ovarian cancer in women

- MSH2, MLH1, and other DNA mismatch repair genes

- HOXB13

Age

One of the biggest risk factors for prostate cancer is age. This disease rarely affects young men. The Prostate Cancer Foundation reports that only 1 in 10,000 men under the age of 40 in the United States will develop it. That number jumps to 1 in 38 for men between the ages of 40 and 59. It leaps to 1 in 14 men between the ages of 60 and 69. The majority of cases are diagnosed in men over 65.

Race and ethnicity

Although the reasons aren’t fully understood, race and ethnicity are risk factors for prostate cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, in the United States, Asian-American and Latino men have the lowest incidences of prostate cancer. In contrast, African-American men are more likely to develop the disease than men of other races and ethnicities. They’re also more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage and have a poor outcome. They’re twice as likely to die from prostate cancer as white men.

Diet

A diet that’s rich in red meat and high-fat dairy products may also be a risk factor for prostate cancer, though there’s limited research. One study published in 2010 looked at 101 cases of prostate cancer and found a correlation between a diet high in meat and high-fat dairy products and prostate cancer, but stressed the need for additional studies.

A more recent study from 2017 looked at the diet of 525 men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer and found an association between high-fat milk consumption and the progression of the cancer. This study suggests that high-fat milk consumption may also play a role in the development of prostate cancer.

Men who eat diets high in meat and high-fat dairy products also seem to eat fewer fruits and vegetables. Experts don’t know if the high levels of animal fat or the low levels of fruits and vegetables contribute more to dietary risk factors. More research is needed.

Geographical location

Where you live can also impact your risk of developing prostate cancer. While Asian men living in America have a lower incidence of the disease than those of other races, Asian men living in Asia are even less likely to develop it. According to the American Cancer Society, prostate cancer is more common in North America, the Caribbean, northwestern Europe, and Australia than it is in Asia, Africa, Central America, and South America. Environmental and cultural factors may play a role.

The Prostate Cancer Foundation notes that in the United States, men living north of 40 degrees latitude are at a higher risk of dying from prostate cancer than those living farther south. This may be explained by a reduction in the levels of sunlight, and therefore vitamin D, which men in northern climates receive. There’s some evidence that vitamin D deficiency may increase risk for prostate cancer.

What are the risk factors for aggressive prostate cancer?

Aggressive prostate cancers may be slightly different than slower-growing types of the disease. Certain risk factors have been linked to the development of more aggressive types of the condition. For example, your risk of developing aggressive prostate cancer may be higher if you:

- smoke

- are obese

- have a sedentary lifestyle

- consume high levels of calcium

Read article on: Causes and Risk Factors of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Complications of Prostate Cancer

The following are the major complications of prostate cancer.

Erectile dysfunction

The nerves that control a man’s erectile response are located very close to the prostate gland. A tumor on the prostate gland or certain treatments such as surgery and radiation can damage these delicate nerves. This can cause problems with achieving or maintaining an erection.

Several effective drugs are available for erectile dysfunction. Oral medications include:

- sildenafil (Viagra)

- tadalafil (Cialis)

- vardenafil (Levitra)

A vacuum pump, also called a vacuum constriction device, can help men who don’t want to take medication. The device mechanically creates an erection by forcing blood into the penis with a vacuum seal.

Urinary Incontinence

Prostatic tumors and surgical treatments for prostate cancer can also lead to urinary incontinence. Someone with urinary incontinence loses control of their bladder and may leak urine or not be able to control when they urinate. The primary cause is damage to the nerves and the muscles that control urinary function.

Men with prostate cancer may need to use absorbent pads to catch leaking urine. Medications can also help relieve irritation of the bladder. In more severe cases, an injection of a protein called collagen into the urethra can help tighten the pathway and prevent leaking.

Metastasis

Metastasis occurs when tumor cells from one body region spread to other parts of the body. The cancer can spread through tissue and the lymph system as well as through the blood. Prostate cancer cells can move to other organs, like the bladder. They can travel even further and affect other parts of the body, such as the bones and spinal cord.

Prostate cancer that metastasizes often spreads to the bones. This can lead to the following complications:

- severe pain

- fractures or broken bones

- stiffness in the hip, thighs, or back

- weakness in the arms and legs

- higher-than-normal levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia), which can lead to nausea, vomiting, and confusion

- compression of the spinal cord, which can lead to muscle weakness and urinary or bowel incontinence

These complications can be treated with drugs called bisphosphonates, or an injectable medication called denosumab (Xgeva).

Prevention of Prostate Cancer

Preventing prostate cancer isn’t possible. Still, taking these steps may reduce your risk:

- Get regular prostate screenings. Ask your healthcare provider how often you should get screened based on your risk factors.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Ask your provider what a healthy weight means for you.

- Exercise regularly. The CDC recommends 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise each week, or a little more than 20 minutes daily.

- Eat a nutritious diet. There’s no one diet to prevent cancer, but good eating habits can improve your overall health. Eat fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Avoid red meats and processed foods.

- Quit smoking. Avoid tobacco products. If you smoke, work with your provider on a smoking cessation program to kick the habit.

Read article on: Complications and Prevention of Liver Cirrhosis

Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer diagnosis often starts with an exam and a blood test. A healthcare professional might do these tests as part of prostate cancer screening. Or you might have these tests if you have prostate cancer symptoms. If these first tests detect something concerning, imaging tests can make pictures of the prostate to look for signs of cancer. To be sure whether you have prostate cancer or not, a sample of prostate cells might be removed for testing. How doctor diagnosed prostate cancer include:

- Prostate cancer screening

- Digital rectal exam

- Prostate-specific antigen test

- Prostate ultrasound

- Prostate MRI

- Prostate biopsy

- Gleason score and grade group

- Prostate cancer biomarker tests

- Imaging tests to look for prostate cancer that has spread

Prostate cancer screening

Prostate cancer screening tests look for prostate cancer in people who don’t have any symptoms of the disease. Tests typically include a prostate-specific antigen blood test and a digital rectal exam.

Most experts recommend talking with your healthcare professional about prostate cancer screening around age 50. Together you can decide whether screening is right for you. You might consider starting the discussions sooner if you’re a Black person, have a family history of prostate cancer or have other risk factors.

Digital rectal exam

A digital rectal exam lets a healthcare professional examine the prostate. It’s sometimes done as part of prostate cancer screening. It might be recommended if your symptoms lead your health professional to think you might have a prostate condition.

During a digital rectal exam, a healthcare professional inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum. The prostate is right by the rectum. The health professional feels the prostate for anything concerning in the texture, shape or size of the gland.

Prostate-specific antigen test

A prostate-specific antigen test is a blood test that measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen in the blood. Prostate-specific antigen, also called PSA, is a substance that prostate cells make. Some PSA circulates in the blood. A PSA test detects the PSA in a blood sample.

Having a high level of PSA in your blood can be a sign of prostate cancer. But many other things also can cause a high PSA level, including prostate infection and prostate enlargement. If a PSA test detects an increased level of PSA in your blood, the test is usually repeated. Your healthcare professional might recommend doing the test again in a few weeks to see if the level goes down. If the level stays high, you might need an imaging test or a biopsy procedure to look for signs of cancer.

A PSA test is often used for prostate cancer screening. It also might be used if you have prostate cancer symptoms. The results can give your healthcare professional clues about your diagnosis.

Prostate ultrasound

Ultrasound is an imaging test that uses sound waves to make pictures of the body. A prostate ultrasound makes pictures of the prostate. A healthcare professional might recommend this test if a digital rectal exam detects something concerning.

To get ultrasound pictures of the prostate, a healthcare professional puts a thin probe into the rectum. The probe uses sound waves to create a picture of the prostate gland. When an ultrasound is done this way, it’s called a transrectal ultrasound.

Prostate MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging, also called MRI, uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create pictures of the inside of the body. A prostate MRI makes pictures of the prostate. It’s often used to look for concerning areas in the prostate that could be cancer.

Prostate MRI images may help your healthcare team decide whether you should have a biopsy procedure to remove prostate tissue for testing. The prostate MRI images also might help with planning the biopsy. If the MRI detects concerning areas in the prostate, the biopsy can target those areas.

During a prostate MRI, you lie on a table that goes into an MRI machine. Most MRI machines are large, tube-shaped magnets. The magnetic field inside the machine works with radio waves and hydrogen atoms in your body to create cross-sectional images.

Healthcare professionals use different kinds of MRI tests for prostate cancer, including:

- Contrast-enhanced MRI. A contrast-enhanced MRI scan uses a dye to make the pictures clearer. A healthcare professional puts the dye into a vein in your arm before the MRI.

- MRI with endorectal coil. MRI with endorectal coil uses a device inserted in the rectum to get better pictures of the prostate. Before this kind of MRI, a healthcare professional inserts a thin wire into your rectum. This thin wire, called an endorectal coil, sends signals to the MRI machine.

- Multiparametric MRI. A multiparametric MRI, also called mpMRI, tells the healthcare team more about the prostate tissue. This kind of MRI can help show the difference between healthy prostate tissue and prostate cancer.

Prostate biopsy

A biopsy is a procedure to remove a sample of tissue for testing in a lab. A prostate biopsy involves removing tissue from the prostate. It’s the only way to know for sure whether there is cancer in the prostate.

A prostate biopsy involves removing prostate tissue with a needle. The needle can go through the skin or through the rectum to get to the prostate. Your healthcare team chooses the kind of prostate biopsy that’s best for you.

Types of prostate biopsy procedures include:

- Transrectal prostate biopsy. A transrectal prostate biopsy is a procedure to get a sample of prostate tissue. It involves putting a needle through the wall of the rectum and into the prostate. This is the most common type of prostate biopsy.During this procedure, a healthcare professional inserts a thin probe into the rectum. The probe makes ultrasound pictures of the rectum. The probe also holds a needle. A healthcare professional uses the ultrasound images to guide the needle. The needle goes through the rectum and into the prostate to remove tissue samples. Samples are removed from different parts of the prostate.

- Perineal prostate biopsy. A perineal prostate biopsy is a procedure to get a sample of prostate tissue. It involves putting a needle through the perineum and into the prostate. The perineum is the area of skin between the scrotum and the anus. This kind of prostate biopsy is less common.During this procedure, a healthcare professional uses an imaging test to help guide the needle. Often this imaging test is an ultrasound. The health professional uses the needle to remove tissue from different parts of the prostate.

Prostate tissue samples go to a lab for testing. In the lab, tests can show whether samples contain cancer.

Prostate biopsy carries a risk of bleeding. Other side effects include blood in the urine and blood in the semen. Sometimes a prostate biopsy causes difficulty urinating or an infection. Side effects may depend on the procedure you have. Ask your healthcare team what you can expect as you recover.

Gleason score and grade group

The Gleason score and grade group are numbers that tell your healthcare team whether your prostate cancer is growing slowly or quickly. How quickly a cancer grows also is called a cancer’s grade.

To decide on the grade, doctors in the lab, called pathologists, look at the prostate cancer cells from a prostate biopsy. If the cancer cells look similar to healthy cells, then the cancer cells are low grade. Low-grade cancer grows slowly. If the cancer cells look very different from healthy cells, then the cancer cells are high grade. High-grade cancer grows quickly.

Prostate cancer grades range from 1 to 5. Grade 1 is very low grade and grade 5 is very high grade. To get the Gleason score, pathologists look at all the prostate biopsy samples to find the grade of each one. They figure out the most common grade found in the samples and the second most common grade. They add these two numbers together to get the Gleason score.

Gleason scores can range from 2 to 10. A score that’s 5 or lower isn’t considered cancer. Gleason scores from 6 to 10 are considered cancer. A Gleason score of 6 means the cancer is growing slowly. A Gleason score of 10 means the cancer is growing quickly.

Pathologists also report the prostate cancer grade as a group. The grade group is another way of stating how quickly the cancer cells are growing. The grade groups for prostate cancer are:

- Grade group 1. This means the Gleason score is 6 or less.

- Grade group 2. This means the Gleason score is 7. The most common grade in the prostate biopsy samples is 3. The second most common grade is 4.

- Grade group 3. This means the Gleason score is 7. The most common grade in the prostate biopsy samples is 4. The second most common grade is 3.

- Grade group 4. This means the Gleason score is 8.

- Grade group 5. This means the Gleason score is 9 or 10.

Your healthcare team uses your grade group to decide on your cancer’s stage. The grade group also can help your care team plan your treatment.

Prostate cancer biomarker tests

Biomarkers are things that can be detected in the body. Results from biomarker tests tell healthcare professionals about what’s going on inside the body. Biomarker testing for cancer looks for biomarkers in the cancer cells. The results help healthcare professionals learn more about what’s going on inside the cancer cells.

Healthcare professionals use prostate cancer biomarker tests to:

- Decide whether to do a prostate biopsy. Some prostate cancer biomarker tests use blood and urine samples to detect signals made by prostate cancer cells. The tests can tell your healthcare team whether a prostate biopsy is likely or not likely to find prostate cancer.

- Decide on a treatment for early prostate cancer. Some prostate cancer biomarker tests involve testing the cancer cells to see if the cancer has a high risk or a low risk of spreading beyond the prostate. If the results of other tests haven’t been clear, this kind of test might help your care team understand your risk. The results can help decide between starting treatment right away or watching the cancer closely to see if it grows.

- Decide on a treatment for advanced prostate cancer. Other prostate cancer biomarker tests help when the cancer is advanced. For prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, the results of these tests can tell your healthcare team whether certain treatments are likely to work on your cancer cells. For this kind of test, your healthcare team may test some of the cells that have spread. The cells might be removed with a biopsy procedure or collected from a blood sample.

Not everyone needs a prostate cancer biomarker test. These tests are new, and healthcare professionals are still deciding how best to use them.

Imaging tests to look for prostate cancer that has spread

Imaging tests can look for signs that the cancer has spread beyond the prostate. These tests might detect cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or to other parts of the body.

Most people with prostate cancer only have cancer in the prostate. They might not need these other imaging tests to look for signs of cancer spread. Ask your healthcare team whether you need these imaging tests.

When prostate cancer spreads beyond the prostate, it might be called metastatic prostate cancer, stage 4 prostate cancer or advanced prostate cancer. Imaging tests used to detect this kind of prostate cancer include:

- A bone scan. A bone scan uses nuclear imaging to make pictures. Nuclear imaging involves using small amounts of radioactive substances, called radioactive tracers. A special camera that can detect the radioactivity also is used along with a computer. The tracer is absorbed more by cells and tissues that are changing. Cancer cells are often growing and changing quickly. Bone scan images can detect places in the bones that absorb the tracer. These may be signs of prostate cancer in the bones.

- A computerized tomography scan. A computerized tomography scan, also called a CT scan, is a type of imaging that uses X-ray techniques to create detailed images of the body. It then uses a computer to create cross-sectional images, also called slices, of the bones, blood vessels and soft tissues inside the body. A CT scan can detect prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other places in the body.

- Magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging, also called MRI, uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create pictures of the inside of the body. An MRI can detect prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other places in the body.

- A positron emission tomography scan. A positron emission tomography scan, also called a PET scan, is a nuclear imaging test. It uses a radioactive tracer that’s injected into a vein. The tracer contains a substance that helps it stick to fast-growing cells, such as cancer cells. The PET images show the places where the tracer builds up. A PET scan can detect prostate cancer that has spread to other places in the body.

- A prostate-specific membrane antigen PET scan. A prostate-specific membrane antigen PET scan also is called a PSMA PET scan. Like other PET scans, this test uses a radioactive tracer. The tracer contains a substance that helps the tracer stick to prostate cancer cells. The substance attaches to a protein that’s found on the surface of prostate cancer cells. A PSMA PET scan can detect prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other places in the body.

Treatment of Prostate Cancer

There are many different ways to treat prostate cancer. The treatment is determined by how advanced the cancer is, whether it has spread outside the prostate, and your overall health. How doctors treat prostate cancer include:

- Active surveillance / Watchful waiting

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Hormone therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

- High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)

- Targeted therapy

- Radiopharmaceutical treatments for prostate cancer

Active surveillance

Prostate cancer usually grows very slowly. This means that you can live a full life without ever needing treatment or experiencing symptoms. If your doctor believes the risks and side effects of treatment outweigh the benefits, they may recommend active surveillance. This is also called watchful waiting or expectant management.

Your doctor will closely monitor the cancer’s progress with blood tests, biopsies, and other tests. If its growth remains slow and doesn’t spread or cause symptoms, it won’t be treated.

Surgery

Surgical treatments for prostate cancer include the following:

Radical prostatectomy

If cancer is confined to the prostate, one treatment option is radical prostatectomy. During this procedure, the prostate gland is completely removed. This can be performed in several ways:

- Open surgery: The surgeon makes a large incision in the lower abdomen or perineum to access the prostate. The perineum is the area between the rectum and the scrotum.

- Laparoscopic surgery: The surgeon uses several specialized cameras and tools to see inside the body and remove the prostate gland through small incisions.

- Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery:

The surgeon controls very precise robotic arms from a computerized control panel to perform laparoscopic surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery is less invasive, as the incisions are smaller. Either laparoscopic or open surgery allows doctors to also examine nearby lymph nodes and other tissues for evidence of cancer.

Loss of the prostate will decrease the amount of fluid in male ejaculate. Men who undergo prostatectomy may experience “dry orgasm” with no emission, as the seminal vesicles that produce a large amount of the fluid of semen are removed during a radical prostatectomy. However, sperm are still produced in the seminiferous tubules within the testes.

Cryosurgery

In this procedure, your doctor will insert probes into the prostate. The probes are then filled with very cold gases to freeze and kill cancerous tissue.

Both cryosurgery and radical prostatectomy are usually done under general anesthesia or regional anesthesia (spinal or epidural anesthesia). General anesthesia puts you completely to sleep during the surgery. Regional anesthesia numbs an area of your body with drugs injected into the spinal canal or epidural space.

Possible side effects of cryosurgery and prostatectomy are urinary incontinence and impotence. The nerves that affect the ability to control urine and get an erection are close to the prostate. These nerves can be damaged during surgery.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

During this surgical procedure, your doctor will insert a long, thin scope with a cutting tool on the end into the penis through the urethra. They will use this tool to cut away prostate tissue that’s blocking the flow of urine. TURP can’t remove the entire prostate. So it can be used to relieve urinary symptoms in men with prostate cancer, just not for trying to cure the cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy kills cancer cells by exposing them to controlled doses of radioactivity. Radiation is often used instead of surgery in men with early-stage prostate cancer that hasn’t spread to other parts of the body. Doctors can also use radiation in combination with surgery. This helps ensure all cancerous tissue has been removed. In advanced prostate cancer, radiation can help shrink tumors and reduce symptoms.

There are two main forms of radiation therapy:

External radiation

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is delivered from outside the body during a series of treatment sessions. There are many different kinds of EBRT therapy. They may use different sources of radiation or different treatment methods.

Examples include intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), which is the most common EBRT for treating prostate cancer, and proton beam radiation therapy.

The latter is less widely available and typically associated with a higher cost. With either type, the goal is to target only the cancerous area and spare adjacent healthy tissue as much as possible.

Internal radiation (also called brachytherapy)

Internal radiation involves surgically implanting radioactive material into the cancerous prostate tissue.

It can be short-term and administered through a catheter, with a high-dose over a few treatments lasting a couple days each. The radioactive media is then removed. Or it can be delivered via implantable pellets (also called seeds) of radioactive material that are permanently left in. These seeds give off radiation for several weeks or months, killing the cancer cells.

The most common side effects of all radiation therapy are bowel and urinary problems like diarrhea and frequent or painful urination. Damage to the tissues surrounding the prostate can also cause bleeding.

Impotence is less common than these, but still a potential side effect, and may be only temporary.

Fatigue is another potential side effect, as is urinary incontinence.

Hormone therapy

Androgens, such as the main male hormone testosterone, cause prostate tissue to grow. Reducing the body’s production of androgens can slow the growth and spread of prostate cancer or even shrink tumors.

Hormone therapy is commonly used when:

- prostate cancer has spread beyond the prostate

- radiation or surgery aren’t possible

- prostate cancer recurs after being treated another way

Hormone therapy alone can’t cure prostate cancer. But it can significantly slow or help to reverse its progress.

The most common type of hormone therapy is a drug or combination of drugs that affects androgens in the body. The classes of drugs used in prostate cancer hormone therapy include:

- Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone

(LHRH) analogs, which prevent the testicles from making testosterone. They are also called

LHRH agonists and GnRH agonists. - LHRH antagonists are another class of

medication that prevents testosterone production in the testicles. - Antiandrogens block the action of androgens in the body.

- Other androgen-suppressing drugs (such

as estrogen) prevent the testicles from making testosterone.

Another hormone therapy option is the surgical removal of the testicles, called orchiectomy. This procedure is permanent and irreversible, so drug therapy is much more common.

Possible side effects of hormone therapy include:

- loss of sex drive

- impotence

- hot flashes

- anemia

- osteoporosis

- weight gain

- fatigue

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of strong drugs to kill cancer cells. It’s not a common treatment for earlier stages of prostate cancer. However, it can be used if cancer has spread throughout the body and hormone therapy has been unsuccessful.

Chemotherapy drugs for prostate cancer are usually given intravenously. They can be administered at home, at a doctor’s office, or in a hospital. Like hormone therapy, chemotherapy typically can’t cure prostate cancer at this stage. Rather, it can shrink tumors, reduce symptoms, and prolong life.

Possible side effects of chemotherapy include:

- fatigue

- hair loss

- loss of appetite

- nausea

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- reduced immune system

function

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is one of the newer forms of cancer treatment. It uses your own immune system to fight tumor cells. Certain immune system cells, called antigen-presenting cells (APCs), are sampled in a laboratory and exposed to a protein that is present in most prostate cancer cells.

These cells remember the protein and are able to react to it and help the immune system’s T-lymphocyte white blood cells know to destroy cells that contain that protein. This mixture is then injected into the body, where it targets the tumor tissue and stimulates the immune system to attack it. This is called the Sipuleucel-T vaccine.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a new cancer treatment that’s being studied in the United States. It uses focused beams of high-frequency sound waves to heat up and kill cancer cells. This method is similar to radiation therapy in that it aims at the focus of the cancer tumor, but doesn’t use radioactive materials.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy for cancer is a treatment that uses medicines that attack specific chemicals in the cancer cells. By blocking these chemicals, targeted treatments can cause cancer cells to die.

For prostate cancer, targeted therapy medicines can help treat cancer that spreads or that comes back after other treatments. Healthcare teams often give targeted therapy medicines with hormone therapy medicines. Sometimes targeted therapy medicines are used alone.

Many targeted therapy medicines exist. Targeted therapy medicines sometimes used for prostate cancer include:

- Niraparib (Zejula).

- Olaparib (Lynparza).

- Rucaparib (Rubraca).

- Talazoparib (Talzenna).

These targeted therapy medicines come as a pill or capsule you swallow. The medicines block the action of enzymes in the cancer cells that help repair breaks in the DNA. These targeted therapy medicines only work in people with certain DNA changes in their cells. To find out if these changes are present in your cells, your healthcare team may test your blood or some of your cancer cells.

Side effects of targeted therapy medicines for prostate cancer include feeling very tired, nausea and loss of appetite. Other side effects include diarrhea, cough, easy bruising and more-frequent infections.

Radiopharmaceutical treatments for prostate cancer

Radiopharmaceutical treatments are medicines that contain a radioactive substance. Radiopharmaceutical treatments used for cancer can deliver radiation to cancer cells.

For prostate cancer, radiopharmaceutical treatments are typically used when the cancer is advanced. People with stage 4 prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, also called metastatic prostate cancer, might consider radiopharmaceutical treatments.

Radiopharmaceuticals used for prostate cancer include:

- Treatments that target PSMA. Radiopharmaceutical treatments can target a protein that’s common on prostate cancer cells called prostate-specific membrane antigen. It’s also called PSMA. One radiopharmaceutical medicine that works in this way is lutetium Lu-177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto). This medicine contains a molecule that finds and sticks to the PSMA on prostate cancer cells. The medicine also contains a radioactive substance. A healthcare professional gives this medicine through a vein. The medicine finds the prostate cancer cells and releases the radiation directly into the cells. PSMA therapy can treat prostate cancer anywhere in the body. This treatment only works if the prostate cancer cells make the PSMA protein. Side effects include dry mouth, nausea and feeling very tired.

- Treatments that target the bones. Some radiopharmaceutical medicines contain a radioactive substance that is attracted to bones. When a healthcare professional puts this medicine into a vein, it travels to the bones and releases the radiation. One medicine that works in this way is radium Ra-223 (Xofigo). Healthcare professionals sometimes use it when prostate cancer spreads to the bones but not to other parts of the body. This treatment can help with bone pain and other symptoms. Side effects include diarrhea and feeling very tired.

Read article on: Diagnosis and Treatment of Leukemia (blood cancer)

The bottom line

Your doctor and healthcare team will help you determine which of these prostate cancer treatments is right for you. Factors include the stage of your cancer, the extent of the cancer, the risk of recurrence, as well as your age and overall health.

Side effects of Prostate Cancer Treatment

Potential side effects include:

- Incontinence: You may leak urine when you cough or laugh or feel an urgent need to pee even when your bladder isn’t full. This problem usually improves over the first six to 12 months without treatment.

- Erectile dysfunction (ED): Surgery, radiation and other treatments can damage the erectile nerves in your penis and affect your ability to get or maintain an erection. It’s common to regain erectile function within a year or two (sometimes sooner). In the meantime, medications like sildenafil (Viagra®) or tadalafil (Cialis®) can help by increasing blood flow to your penis.

- Infertility: Treatments can affect your ability to produce or ejaculate sperm, resulting in infertility. If you want children in the future, you can preserve sperm in a sperm bank before starting treatment. After treatments, you may undergo sperm extraction. This procedure involves removing sperm directly from testicular tissue and implanting it into your partner’s uterus.

Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re experiencing treatment side effects. Often, they can recommend medicines and procedures that can help.

Conclusion

With early diagnosis and treatment, prostate cancer is often highly curable. Many people diagnosed when the cancer hasn’t spread beyond their prostate go on to live normal, cancer-free lives for several years following treatment. Still, for a small number of people, the disease can be aggressive and spread quickly to other body parts. Your healthcare provider can discuss the best screening schedule based on your risk factors. They can recommend the best treatment options based on how slow growing or aggressive your cancer is.

Subscribe YouTube Channel

- Subscribe Medmichihealthcare YouTube channel

- List of Common Diseases & Medical Disorders

- Buy Complete Premium Anatomy Notes (PDFs)

- Medmichihealthcare New posts

- Read All causes of disease short notes

- Read All diagnosis of disease short notes

- Read All treatment of disease short notes

Discover more from Medmichihealthcare

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.