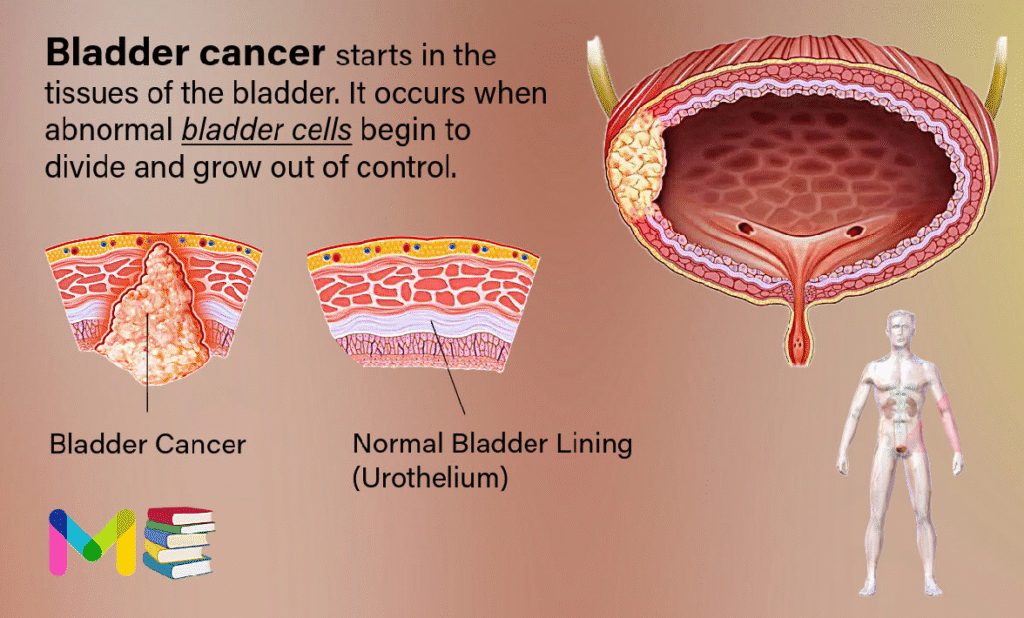

Bladder cancer starts in the tissues of the bladder. It occurs when abnormal bladder cells begin to divide and grow out of control. They may form a tumor and, with time, spread to surrounding muscles and organs.

While other types of cancer may spread to the bladder, cancer is named for the location where it starts.

In the United States, doctors diagnose approximately 60,000 males and 18,000 females per year with the disease. Worldwide, it is the 7th most common type of cancer.

The bladder is a hollow muscular organ in your lower abdomen that stores urine.

Bladder cancer most often begins in the cells (urothelial cells) that line the inside of your bladder. Urothelial cells are also found in your kidneys and the tubes (ureters) that connect the kidneys to the bladder. Urothelial cancer can happen in the kidneys and ureters, too, but it’s much more common in the bladder.

Most bladder cancers are diagnosed at an early stage, when the cancer is highly treatable. But even early-stage bladder cancers can come back after successful treatment. For this reason, people with bladder cancer typically need follow-up tests for years after treatment to look for bladder cancer that recurs.

Table of Contents

Types of bladder cancer

There are several types of bladder cancer. Each type is named for the cells that line the wall of your bladder where the cancer started. Bladder cancer types include:

- Transitional cell carcinoma: This cancer starts in transitional cells in the inner lining of your bladder wall. About 90% of all bladder cancers are transitional. In this cancer type, abnormal cells spread from the inner lining to other layers deep in your bladder or through your bladder wall into fatty tissues that surround your bladder. This bladder cancer type is also known as urothelial bladder cancer.

- Squamous cell carcinoma: Squamous cells are thin, flat cells that line the inside of your bladder. This bladder cancer accounts for about 5% of bladder cancers and typically develops in people who’ve had long bouts of bladder inflammation or irritation.

- Adenocarcinoma: Adenocarcinoma cancers are cancers in the glands that line your organs, including your bladder. This is a very rare type of bladder cancer, accounting for 1% to 2% of all bladder cancers.

- Small cell carcinoma of the bladder: This extremely rare type of bladder cancer affects about 1,000 people in the U.S.

- Sarcoma: Rarely, soft tissue sarcomas start in bladder muscle cells.

Healthcare providers may also categorize bladder cancer as being noninvasive, non-muscle-invasive or muscle-invasive.

- Noninvasive: This bladder cancer may be tumors in a small section of tissue or cancer that’s only on or near the surface of your bladder.

- Non-muscle-invasive: This refers to bladder cancer that’s moved deeper into your bladder but hasn’t spread to muscle.

- Muscle-invasive: This bladder cancer has grown into bladder wall muscle and may have spread into the fatty layers or tissues on organs outside of your bladder.

Stages of bladder cancer

Doctors use a staging system to communicate how far the cancer has spread within your bladder, lymph nodes, and other organs. There are multiple staging systems for bladder cancer. Stages can include:

- Stage 0: The cancer hasn’t spread past the lining of the bladder

- Stage 1: The cancer has spread past the lining of the bladder, but it hasn’t reached the layer of muscle in the bladder

- Stage 2: The cancer has spread to the layer of muscle in the bladder

- Stage 3: The cancer has spread into the tissues that surround the bladder

- Stage 4: The cancer has spread past the bladder to the neighboring areas of the body

The stage may also be subdivided to more specifically describe the cancer’s spread.

A more sophisticated and preferred staging system is TNM, which stands for tumor, node involvement and metastases. In this system:

- Invasive bladder tumors can range from T2 (the tumor spreads to your main muscle wall below the lining) all the way to T4 (it spreads beyond your bladder to nearby organs or your pelvic side wall).

- Lymph node involvement ranges from N0 (no cancer in lymph nodes) to N3 (cancer in many lymph nodes, or in one or more bulky lymph nodes larger than 5 centimeters).

- M0 means that there isn’t any metastasis (spread) outside of your pelvis. M1 means that it has metastasized outside of your pelvis.

You can also read: Types & Stages of Colon (colorectal cancer)

Symptoms of bladder cancer

Bladder cancer can cause symptoms that vary from person to person. These may include:

- blood in the urine, which may be rust-colored, bright red, or may not be visible

- painful urination

- having to pee more than usual (frequent urination)

- having a sudden and overwhelming urge to pee (urgent urination)

- losing control of your bladder (urinary incontinence)

Bladder cancer may also cause symptoms that affect other parts of the body, particularly if the cancer has spread beyond the bladder. These can include:

- pain in the abdominal area

- pain in the lower back on one side of the body

- fatigue

- unintentional weight loss

- loss of appetite

- bone pain or tenderness

- swollen feet

When to see a healthcare provider?

If you notice that you have discolored urine and are concerned it may contain blood, make an appointment with your doctor to get it checked. Also make an appointment with your doctor if you have other signs or symptoms that worry you.

Causes of bladder cancer

Bladder cancer begins when cells in the bladder develop changes (mutations) in their DNA. A cell’s DNA contains instructions that tell the cell what to do. The changes tell the cell to multiply rapidly and to go on living when healthy cells would die. The abnormal cells form a tumor that can invade and destroy normal body tissue. In time, the abnormal cells can break away and spread (metastasize) through the body.

While certain factors can increase your risk for the kind of DNA damage that causes these mutations, mutations may also occur at random. People can develop bladder cancer without having known risk factors, while others who have multiple bladder cancer risk factors may not develop bladder cancer at all.

You can also read: Symptoms & Causes of Prostate Cancer

Risk factors of bladder cancer

Some factors may increase your risk of developing bladder cancer. These can include:

- smoking cigarettes

- exposure to cancer-causing chemicals (carcinogens), such as petroleum, rubber, metals, paint products, dyes, or diesel fumes

- a family history of bladder cancer

- having certain genetic changes

- having schistosomiasis, a bladder infection caused by a specific parasite

- drinking water contaminated with arsenic or chlorine

- certain herbal medicines and supplements

- previous treatment with the chemotherapy drugs cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) or ifosfamide (Ifex)

- prior radiation therapy to treat cancer in the pelvic area

- chronic bladder infections or long-term use of urinary catheters

- not drinking enough fluids

- having a bladder defect

People who smoke cigarettes may be at least three times more likely to develop bladder cancer than people who do not smoke.

Bladder cancer also tends to occur more often in certain groups of people. You may have a higher risk of developing it if you are:

- assigned male at birth

- age 55 or older

- white

Prevention of bladder cancer

Because doctors don’t yet know what exactly causes bladder cancer, it may not be preventable in all cases. The following factors and behaviors may help reduce your risk of getting bladder cancer:

- not smoking, or quitting smoking if you smoke

- avoiding secondhand cigarette smoke

- avoiding exposure to carcinogenic chemicals and wearing appropriate safety equipment when working with carcinogenic chemicals

- drinking plenty of water

You can also read: Risk Factors & Prevention of Lung cancer

Diagnosis of bladder cancer

Tests and procedures used to diagnose bladder cancer may include:

- Using a scope to examine the inside of your bladder (cystoscopy). To perform cystoscopy, your doctor inserts a small, narrow tube (cystoscope) through your urethra. The cystoscope has a lens that allows your doctor to see the inside of your urethra and bladder, to examine these structures for signs of disease. Cystoscopy can be done in a doctor’s office or in the hospital.

- Removing a sample of tissue for testing (biopsy). During cystoscopy, your doctor may pass a special tool through the scope and into your bladder to collect a cell sample (biopsy) for testing. This procedure is sometimes called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). TURBT can also be used to treat bladder cancer.

- Examining a urine sample (urine cytology). A sample of your urine is analyzed under a microscope to check for cancer cells in a procedure called urine cytology.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests, such as computerized tomography (CT) urogram or retrograde pyelogram, allow your doctor to examine the structures of your urinary tract.

During a CT urogram, a contrast dye injected into a vein in your hand eventually flows into your kidneys, ureters and bladder. X-ray images taken during the test provide a detailed view of your urinary tract and help your doctor identify any areas that might be cancer. Retrograde pyelogram is an X-ray exam used to get a detailed look at the upper urinary tract. During this test, your doctor threads a thin tube (catheter) through your urethra and into your bladder to inject contrast dye into your ureters. The dye then flows into your kidneys while X-ray images are captured.

Determining the extent of the cancer

After confirming that you have bladder cancer, your doctor may recommend additional tests to determine whether your cancer has spread to your lymph nodes or to other areas of your body.

Tests may include:

- CT scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET)

- Bone scan

- Chest X-ray

Your doctor uses information from these procedures to assign your cancer a stage.

Bladder cancer grade

Bladder cancers are further classified based on how the cancer cells appear when viewed through a microscope. This is known as the grade, and your doctor may describe bladder cancer as either low grade or high grade:

- Low-grade bladder cancer. This type of cancer has cells that are closer in appearance and organization to normal cells (well differentiated). A low-grade tumor usually grows more slowly and is less likely to invade the muscular wall of the bladder than is a high-grade tumor.

- High-grade bladder cancer. This type of cancer has cells that are abnormal-looking and that lack any resemblance to normal-appearing tissues (poorly differentiated). A high-grade tumor tends to grow more aggressively than a low-grade tumor and may be more likely to spread to the muscular wall of the bladder and other tissues and organs.

Treatment of bladder cancer

A doctor will work with you to determine the best treatment based on the type and stage of your cancer, your symptoms, and your overall health.

Treatment for stage 0 and stage 1

Treatment for stage 0 and stage 1 bladder cancer may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- chemotherapy

- immunotherapy, which involves taking a medication that causes your immune system to attack the cancer cells

Treatment for stage 2 and stage 3

Treatment for stage 2 and stage 3 bladder cancer may include:

- removal of part of the bladder

- removal of the whole bladder (radical cystectomy) followed by surgery to create a new way for urine to exit the body

- chemotherapy

- radiation therapy

- immunotherapy

A doctor may recommend chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy for multiple purposes, including to:

- shrink the tumor before surgery

- treat cancer when surgery isn’t an option

- treat remaining cancer cells after surgery

- prevent cancer from recurring

Treatment for stage 4 bladder cancer

Treatment for stage 4 bladder cancer may include:

- radical cystectomy and removal of the surrounding lymph nodes, followed by surgery to create a new way for urine to exit the body

- chemotherapy

- radiation therapy

- immunotherapy

- clinical trial drugs

Depending on your overall health, treatment may focus on removing cancer cells or relieving your symptoms and extending your life.

You may also choose to participate in a clinical trial to test new treatments and new combinations of existing treatments.

Approaches to bladder cancer surgery might include:

- Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). TURBT is a procedure to diagnose bladder cancer and to remove cancers confined to the inner layers of the bladder — those that aren’t yet muscle-invasive cancers. During the procedure, a surgeon passes an electric wire loop through a cystoscope and into the bladder. The electric current in the wire is used to cut away or burn away the cancer. Alternatively, a high-energy laser may be used.Because doctors perform the procedure through the urethra, you won’t have any cuts (incisions) in your abdomen.As part of the TURBT procedure, your doctor may recommend a one-time injection of cancer-killing medication (chemotherapy) into your bladder to destroy any remaining cancer cells and to prevent cancer from coming back. The medication remains in your bladder for a period of time and then is drained.

- Cystectomy. Cystectomy is surgery to remove all or part of the bladder. During a partial cystectomy, your surgeon removes only the portion of the bladder that contains a single cancerous tumor.A radical cystectomy is an operation to remove the entire bladder and the surrounding lymph nodes. In men, radical cystectomy typically includes removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles. In women, radical cystectomy may involve removal of the uterus, ovaries and part of the vagina.Radical cystectomy can be performed through an incision on the lower portion of the belly or with multiple small incisions using robotic surgery. During robotic surgery, the surgeon sits at a nearby console and uses hand controls to precisely move robotic surgical instruments.

- Neobladder reconstruction. After a radical cystectomy, your surgeon must create a new way for urine to leave your body (urinary diversion). One option for urinary diversion is neobladder reconstruction. Your surgeon creates a sphere-shaped reservoir out of a piece of your intestine. This reservoir, often called a neobladder, sits inside your body and is attached to your urethra. The neobladder allows most people to urinate normally. A small number of people difficulty emptying the neobladder and may need to use a catheter periodically to drain all the urine from the neobladder.

- Ileal conduit. For this type of urinary diversion, your surgeon creates a tube (ileal conduit) using a piece of your intestine. The tube runs from your ureters, which drain your kidneys, to the outside of your body, where urine empties into a pouch (urostomy bag) you wear on your abdomen.

- Continent urinary reservoir. During this type of urinary diversion procedure, your surgeon uses a section of intestine to create a small pouch (reservoir) to hold urine, located inside your body. You drain urine from the reservoir through an opening in your abdomen using a catheter a few times each day.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy drugs focus on specific weaknesses present within cancer cells. By targeting these weaknesses, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Your cancer cells may be tested to see if targeted therapy is likely to be effective.

Targeted therapy may be an option for treating advanced bladder cancer when other treatments haven’t helped.

Bladder preservation

In certain situations, people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer who don’t want to undergo surgery to remove the bladder may consider trying a combination of treatments instead. Known as trimodality therapy, this approach combines TURBT, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

First, your surgeon performs a TURBT procedure to remove as much of the cancer as possible from your bladder while preserving bladder function. After TURBT, you undergo a regimen of chemotherapy along with radiation therapy.

If, after trying trimodality therapy, not all of the cancer is gone or you have a recurrence of muscle-invasive cancer, your doctor may recommend a radical cystectomy.

After bladder cancer treatment

Bladder cancer may recur, even after successful treatment. Because of this, people with bladder cancer need follow-up testing for years after successful treatment. What tests you’ll have and how often depends on your type of bladder cancer and how it was treated, among other factors.

In general, doctors recommend a test to examine the inside of your urethra and bladder (cystoscopy) every three to six months for the first few years after bladder cancer treatment. After a few years of surveillance without detecting cancer recurrence, you may need a cystoscopy exam only once a year. Your doctor may recommend other tests at regular intervals as well.

People with aggressive cancers may undergo more-frequent testing. Those with less aggressive cancers may undergo testing less often.

You can also read: Diagnosis & Treatment of Leukemia

Conclusion

Bladder cancer begins in the tissue of the bladder. It can cause urinary symptoms, such as urgency and frequency, and systemic symptoms, such as fatigue.

Treatment and outlook can depend on the stage of your bladder cancer and other factors, including your age and overall health.

If you have bladder cancer, it may help to know about half of all people with the condition receive treatment when their tumors are limited to the inner layer of their bladder wall. For them, surgery to remove tumors means they’re cancer-free. But bladder cancer often comes back (recurs).

If you’re worried about recurring cancer, talk to your healthcare provider. They’re your best resource for information on risk factors that increase the chance you’ll have another bout of bladder cancer. They’ll help you stay vigilant about symptoms that may be signs of recurring bladder cancer and be there for you if you need more bladder cancer treatment.

- List of Common Diseases & Medical Disorders

- Buy Complete Premium Anatomy Notes (PDFs)

- Medmichihealthcare New posts

- Read All causes of disease short notes

- Read All diagnosis of disease short notes

- Read All treatment of disease short notes

- Subscribe Medmichihealthcare YouTube channel

Discover more from Medmichihealthcare

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.